Why are trusts so widely used in Australia?

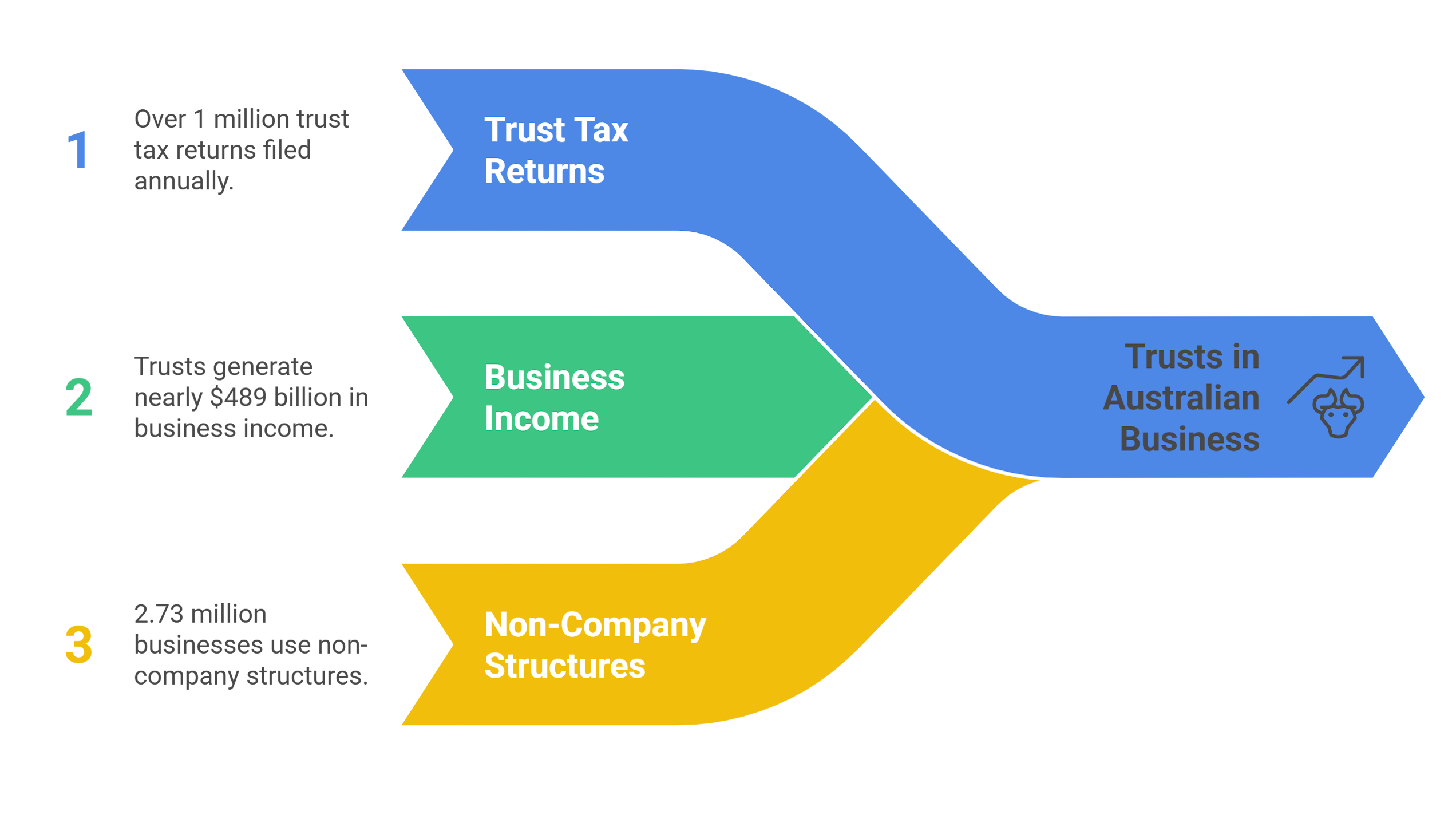

Trusts are widely used in Australia, with close to one million trust returns lodged and hundreds of billions of dollars flowing through trusts each year.

Trusts play a central role in the Australian business and investment landscape. The Australian Taxation Office reported 1,022,229 trust tax returns for 2022–23, with total business income of approximately $489 billion across the trust population. At the same time, the Australian Bureau of Statistics recorded 2.73 million actively trading businesses at 30 June 2025, underscoring how common non-company structures remain in practice.

These figures explain why trusts continue to feature heavily in business structuring, succession planning, and investment ownership—particularly for family groups, founders, and privately held enterprises.

This guide explains the practical “how it works” of trusts (not theory), with added sections on:

- Trust tax rates for 2025–26

- Family trust vs unit trust comparison

- Trust distribution strategies

- Section 100A (reimbursement agreement) considerations

- Annual trust compliance requirements

- When a trust structure makes sense for Melbourne SMEs

General information only. Trust outcomes depend on the deed, the facts, and current law. Get advice before implementing.

What is a trust structure in Australia?

A trust is a legal relationship in which a trustee holds assets under a trust deed and must manage them for the beneficiaries.

A trust is best understood as a fiduciary obligation, not a separate legal person like a company.

A trust is not a separate legal entity like a company. Instead, it’s a relationship created (usually) by a trust deed.

- The trustee holds legal title to the assets.

- The beneficiaries are the people/entities who can benefit from income and/or capital.

- The trust deed defines the rules: who can benefit, what “income” means, what the trustee can do, and how decisions must be documented.

- Many modern trusts also have an appointor (or principal) who controls who the trustee is. That control matters for succession and governance.

Trustee: why a corporate trustee is common

In most commercial contexts, a corporate trustee is used because trustees can be personally liable for trust debts. A corporate trustee can help ring-fence liability (not eliminate risk—personal guarantees can still override structure).

Why are trusts so widely used in Australia?

Trusts are widely used because they provide flexible distributions, succession control, and practical ways to hold business and investments.

Trusts tend to be used where at least one of these is true:

- Distribution flexibility matters

A discretionary trustee can allocate income among eligible beneficiaries (subject to the deed and integrity rules). - Control and succession need to be managed

Control commonly sits with the trustee and appointor. That can allow succession changes without transferring legal ownership of assets every time family circumstances change. - Business and investment are held in the same group

Many private groups use trusts to hold business interests, investments, or property. The structure can support family governance if run well. - Multiple entities are used together

It’s common to see a trust and a company working as a combined structure—for example, a discretionary trust owning shares in a trading company.

What types of trusts are commonly used in Australia?

Most Australian business trusts are either discretionary or unit trusts, depending on whether flexibility or fixed entitlements are required.

The most common trust types used in practice include:

-

Discretionary trusts (often called “family trusts”)

A discretionary trust gives the trustee discretion to decide which beneficiaries receive income and/or capital each year. This flexibility is why discretionary trusts are common for founder-led family groups.

-

Unit trusts

A unit trust has fixed entitlements—like shares. If you own 50% of the units, you are generally entitled to 50% of distributions (subject to deed terms). Unit trusts are common in joint ventures and property arrangements where ownership must stay proportional.

-

Family trusts (tax meaning)

“Family trust” is used casually to mean a discretionary trust, but in tax, it can also refer to a trust that has made a Family Trust Election (FTE). An FTE can simplify certain tax issues, but it restricts who can benefit without triggering a penalty tax.

-

Service trusts (professional firms)

Service trusts can be used for staffing, leasing, or equipment arrangements—particularly in professional practices. They need strong commercial support and careful compliance.

Each structure solves a different problem. Choosing the wrong one often creates complexity rather than clarity.

What is a family (discretionary) trust and how does it work?

A family trust is usually a discretionary trust where the trustee decides each year which eligible beneficiaries receive income or capital.

In practice, a discretionary trust works like this:

- The trust earns income (business profits, rent, dividends, capital gains).

- Before year end (often by 30 June), the trustee decides who will be made entitled to that income.

- The trust lodges a tax return, showing its net income and how income is allocated.

- Beneficiaries include their share in their tax returns (if they’re presently entitled), or the trustee may be assessed in some cases.

Important: “We’ll decide later” is usually not a strategy. Trust tax outcomes often depend on making valid decisions and records on time.

For founders and early-stage businesses, this decision often overlaps with broader structure planning. We explore these trade-offs in more detail in our guide on

startup accounting in Australia: choosing the right business structure.

Where does the risk really sit in a trust structure?

Trusts can reduce risk concentration, but trustee liability, guarantees, and control issues mean asset protection is never absolute.

Three risk areas matter most:

Trustee liability

Trustees are generally personally liable for trust debts. This is why a corporate trustee is commonly used where the trust undertakes commercial activities or borrows money.

Personal guarantees

Bank and landlord guarantees frequently override structural protection. Even the best structure cannot undo a personal guarantee once given.

Control and “ownership” risk

Where one individual effectively controls the trustee, courts may treat trust interests as property in certain insolvency or family law contexts. Control, not labels, often determines outcomes.

Practical takeaway: Avoid holding high-risk trading assets and long-term passive investments in the same trust where asset protection is a genuine objective.

Family trust vs unit trust: what’s the difference?

Family trusts allow flexible distributions; unit trusts provide fixed entitlements and clearer governance for joint ventures and co-owners.

Quick comparison (SME-practical)

| Feature | Family / discretionary trust | Unit trust |

|---|---|---|

| Economic entitlements | Flexible | Fixed (by units) |

| Best for | Single-family group | Joint ventures, unrelated parties |

| Income distribution | Trustee discretion | Proportional to units |

| Governance | Can be simpler, but must be disciplined | More formal (units, transfers, valuation) |

| Common risk point | Documentation, 100A integrity | Transfers, buy/sell, entitlement clarity |

When unit trusts are usually the cleaner fit

A unit trust is often preferred when:

- Unrelated parties invest together

- Ownership must remain fixed

- Lenders/partners want “share-like” clarity

- You need clearer entry/exit mechanics

Who pays tax on trust income?

Trust tax usually follows present entitlement: beneficiaries are taxed if entitled, otherwise the trustee may be assessed.

The central tax concept for trusts is present entitlement:

-

If a beneficiary is made presently entitled to trust income, they are generally assessed on that share.

-

If income is not effectively dealt with, the trustee may be taxed, often at the top marginal rate under section 99A.

Family Trust Elections can simplify some outcomes, but they also restrict who can receive distributions without triggering penalty tax. Flexibility comes with boundaries.

What are the trust tax rates for 2025–26?

Trusts don’t have one flat tax rate. Beneficiaries pay at their rates, or trustees may be taxed at top rates in some cases.

If beneficiaries are assessed: 2025–26 resident rates (summary)

For Australian residents (18+), 2025–26 marginal rates are:

- $0–$18,200: Nil

- $18,201–$45,000: 16c per $1 over $18,200

- $45,001–$135,000: $4,288 + 30c per $1 over $45,000

- $135,001–$190,000: $31,288 + 37c per $1 over $135,000

- $190,001+: $51,638 + 45c per $1 over $190,000

These figures exclude the Medicare levy, which is often an additional consideration.

If the trustee is assessed, why do people call it the “penalty rate”

Where the trustee is assessed under provisions like section 99A, it is commonly at (or aligned to) the top marginal outcomes, which is why missed resolutions and integrity problems can be expensive.

Practical takeaway: The real tax question is rarely “what is the trust tax rate?” It’s “who will be assessed, on what amount, and was it documented correctly?”

What must trustees do before 30 June each year?

Most discretionary trusts require a compliant distribution resolution by 30 June to avoid trustee-rate tax outcomes.

For many discretionary trusts, income does not “automatically” flow to beneficiaries. Trustees typically must:

- Check the deed’s definition of trust income

Some deeds define income differently to tax law. This affects what can be distributed and how. - Confirm who is eligible to receive distributions

Beneficiary eligibility is deed-driven. Mistakes here are common. - Prepare a valid trustee resolution

This often needs to be made by 30 June (or earlier if the deed requires it), and it must be consistent with deed requirements. - Document streaming correctly (if used)

Streaming capital gains and franked distributions is technical and deed dependent. - Keep the file audit-ready

If a distribution is later questioned, the quality of records matters as much as the intended outcome.

Most trust problems arise here—not from aggressive planning, but from poor documentation and timing.

How do trust distributions work, and what strategies are common?

Trust distributions must follow the deed and be documented on time. Strategies allocate income to intended beneficiaries within integrity rules.

A trust distribution strategy is not about cleverness. It’s about matching:

- the deed’s rules,

- the group’s real cash needs,

- the tax position of beneficiaries,

- and the integrity rules (especially Section 100A).

Strategy 1: Distribute to beneficiaries who actually benefit

This is the “cleanest” strategy because it aligns entitlement, cash benefit, and records.

Example (simplified):

A discretionary trust earns $220,000 from a family business. A spouse is actively working in the business and needs cash for household costs. A distribution to that spouse can be commercially consistent—provided the deed allows it, and it’s documented correctly.

Strategy 2: Avoid “tax bills without cash”

Trusts can create a tax liability for a beneficiary even if the trust retains cash for working capital. If you do this, you need a deliberate plan for:

- how the beneficiary’s tax bill is funded, and

- how the entitlement is recorded (not hand-waved).

Strategy 3: Use group entities intentionally (not by habit)

Some groups use a company beneficiary to manage how much income is taxed at individual rates vs company rates. This can be effective, but it introduces governance and integrity considerations (including how entitlements are managed).

Strategy 4: Plan distributions before June, not after

The worst “strategy” is leaving trust decisions to late June with incomplete accounts. Good outcomes usually need:

- estimated taxable profit,

- clarity on income types,

- and enough time to verify beneficiary eligibility.

Tax planning support: Tax Planning Melbourne | Proactive Strategies for SMEs – 42 Advisory

When is a unit trust a better fit?

Unit trusts suit joint ventures or multiple family groups where fixed economic interests and clearer governance are required.

Unit trusts are commonly used where:

-

Multiple unrelated parties or family groups invest together

-

Fixed ownership percentages must be maintained

-

Governance expectations are more formal

They can still offer flow-through taxation, but changes in unit holdings and distributions often carry additional tax consequences, requiring careful advice.

What is Section 100A and when does it matter for trusts?

Section 100A can apply when a beneficiary is made entitled to trust income but someone else effectively benefits from that entitlement.

Section 100A is an integrity rule that can apply where there is a “reimbursement agreement” connected to a beneficiary’s entitlement to trust income. The ATO has published its view in TR 2022/4 and a compliance approach in PCG 2022/2.

The pattern the ATO worries about (in plain English)

Not every family arrangement is a problem. But risk rises where:

- income is appointed to a beneficiary (often lower-tax),

- yet someone else receives the benefit (directly or indirectly),

- or the entitlement exists mainly to reduce tax, not to provide a genuine benefit.

CPA Australia has also flagged the need for care in family trust distributions given ATO focus in this area.

Practical “risk indicators” trustees should treat as review triggers

- Adult children are appointed income, but they don’t receive funds and don’t control/benefit.

- Trust money consistently ends up paying another person’s expenses.

- There’s an informal understanding that entitlements will be “returned”, offset, or redirected.

- Records do not clearly show who benefited and how.

Practical controls that reduce risk

- Make distributions that reflect genuine intended benefit.

- Keep records that match reality (minutes, bank flows, loan account support).

- Avoid repeating the same pattern every year if circumstances change.

- Treat “adult beneficiary distributions with no cash benefit” as a governance item, not a default.

What trust compliance requirements apply each year?

Trust compliance includes a valid deed, trustee resolutions, accurate beneficiary reporting, annual tax lodgment, and records showing who benefited.

A practical annual compliance checklist:

Annual governance

- Trust deed and variations are current, signed, and stored.

- Trustee details are correct (especially if corporate trustee changes).

- Appointor/controller succession is documented.

Annual tax and reporting

- Trust has its own TFN and lodges an annual trust tax return.

- Beneficiary reporting is accurate and consistent with resolutions.

- Workpapers support the calculation of distributable income and taxable net income.

Records that prevent most disputes

- Signed trustee minutes/resolutions

- Financial statements and supporting schedules

- Bank statements showing distributions or movements

- Loan accounts where entitlements are unpaid (with clear rationale and tracking)

Accounting systems and reporting support: Small Business Accounting Services Melbourne | Fixed-Fee – 42 Advisory

Trust vs company: how should you choose?

Trusts offer distribution flexibility; companies support retained profits and clearer governance—many groups use both together.

As a broad rule:

-

Trusts suit variable profit sharing and succession flexibility

-

Companies suit profit retention, reinvestment, and corporate governance

Many established groups combine both—for example, a discretionary trust owning shares in a trading company. The “right” answer depends on risk, growth plans, and who needs access to profits over time.

If your business operates in the startup or scale-up space, structure decisions should be integrated with tax, systems, and funding strategy. Our startup accounting and advisory services in Melbourne are designed around that integrated approach.

What are the most common trust mistakes?

Most trust failures are governance failures: outdated deeds, wrong beneficiaries, late resolutions, and mixing risky and passive assets.

Common issues include:

-

Deeds that no longer support intended tax outcomes

-

Distributions to non-beneficiaries

-

Late or defective trustee resolutions

-

Underestimating trustee and guarantee risk

-

No documented succession for control roles like the appointor

None of these are theoretical problems—they are practical, recurring causes of disputes and adverse tax outcomes.

Final thought

Trusts remain powerful tools in Australia, but they are not set-and-forget structures. When used thoughtfully, they support flexibility, succession, and long-term planning. When governance is weak, they often amplify risk instead of reducing it.

YOU MAY NEED TO KNOW

Frequently Asked Questions

Are trusts legal in Australia?

Yes. Trusts are recognised legal relationships in Australia and are widely used to hold business and investment assets under a trust deed.

Do trusts pay a single tax rate?

No. Trust tax depends on who is entitled to the income. Beneficiaries pay at their rates, or trustees may be assessed in some cases.

What happens if a trust doesn’t distribute by 30 June?

If a valid resolution isn’t made on time, the trustee may be assessed on some or all net income, often at high marginal outcomes.

What is Section 100A in simple terms?

Section 100A may apply if a beneficiary is made entitled to income under an arrangement where another person effectively receives the benefit.

Is a corporate trustee always required?

Not always, but corporate trustees are common because they can help manage trustee liability in commercial contexts, especially where debt exists.

When is a unit trust better than a family trust?

Unit trusts are often better for joint ventures where ownership must be fixed and proportional, especially for unrelated investors or co-owners.